The Body and the Mind: Understanding the Two Fronts of HIV

By: Erica Lee

Exploring the physical and cellular mechanisms of infection allows for a glimpse of the extensive effects of HIV infection on a patient. HIV, once inside the body’s cells, will never leave and cannot be cured once it takes its hold. It both actively multiplies inside thousands of cells and lies dormant in millions more, making it impossible to eradicate.

Cellular Mechanisms of Infection

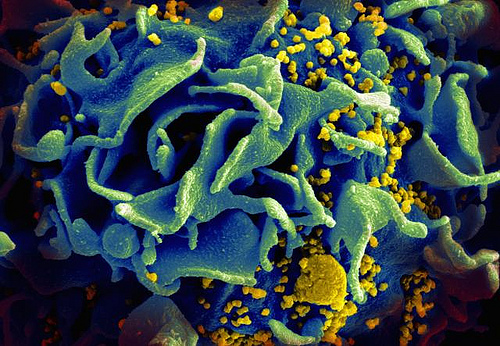

HIV is first introduced into the body through the common methods of STI transmission: sexual contact, contact with infected blood and perinatal transmission, which is a transmission from mother to child through breast milk from an HIV+ mother. HIV, like any other virus, is nonliving and must hijack a host’s cells to replicate itself. Once introduced to the body, the virus goes searching for a special type of cell: T helper cells. These are a kind of white blood cell that protects against infection by identifying foreign bodies using receptors on their surfaces. This is what makes HIV especially potent–it does not just disable the cells that are supposed to prevent infections. It adds insult to injury and uses them to multiply the infection itself. HIV has protein structures on the outside of its membrane that fit into matching receptors on T cells like keys into a lock. Once the “key” is inserted, the T cell engulfs the virus by phagocytosis and takes it into the cell. Once inside, HIV produces a strand of viral DNA to insert into the host’s DNA; almost akin to inserting a recipe for a time bomb in the middle of the recipe the host cell was going to use for dinner. The T cell doesn’t realize anything is wrong and keeps reading the DNA and using it to build proteins for its own use. This means that whenever the T cell makes proteins for itself, it also makes copies of the virus, which then go out and infect more T cells.

This can go on for years without damaging the cells, which is why many people are HIV+ but do not yet have AIDS. AIDS develops when the HIV mutates to have a different “key” protein for a different “lock” receptor on the surface of the T cell. It goes through the same process of replication as the original virus, but when it goes to leave the cell, something goes wrong. When it leaves, it ruptures the host cell’s plasma membrane, killing an otherwise perfectly healthy T cell that now cannot identify foreign bodies. The mutated virus tears throughout the body, leaving millions of T cells dead in its wake. This cripples the body’s immune system and prevents it mortally vulnerable to something as mild as a common cold.

Treatment and Care

While there is no cure for HIV, modern medicine has allowed patients who test positive for HIV to have a longer, healthier life than if they had gone untreated. These drugs are usually referred to as antiretroviral drugs and interfere with most aforementioned crucial pathways during the HIV life cycle, disabling HIV’s ability to enter the cell, copying its own DNA and inserting into the host cell’s DNA. However, while these interact with actively proliferating HIV, many more HIV lay dormant in cells and can grow resistant to these drugs.

Recent Advancements in HIV Medicine

When cells are usually infected, they self-destruct to contain the infection. However, when HIV infects these T helper cells, it disables this suicide pathway so it can use the host cell to produce more of the virus. A drug called Ciclopirox has been shown in cell cultures to destroy the mitochondria of HIV-infected cells. Ciclopirox is currently used as a topical antifungal medication to fight yeast infections of the skin, ringworm, athlete’s foot and certain kinds of dandruff. However, Ciclopirox is only FDA approved for topical use and clinical trials have not yet begun to test its efficacy in the human bloodstream, where it would have to be administered to be effective.

A compound that may be closer to clinical trials is a toxin in bee venom called melittin. Scientists take the toxin and mount it into nanoparticles–tiny pincushion-like structures with two layers of “pins.” Scientists place benign bumper particles on the outer pin-like layer and place the toxin on the smaller pins. The bumpers protect the larger human cells from interacting with the poison, but HIV floats right past them and into the melittin, which shreds HIV’s protective double membrane and renders it harmless even before it could infect a T helper cell. Researchers believe nanoparticles may soon be available for clinical trials.

One lucky girl hopefully will never need either of these treatments. Pregnant women who test HIV+ are usually given medicine to prevent the infection from spreading to the fetus. However, one mother did not know she was HIV+ and gave birth to an HIV+ daughter. Dr. Hannah Gay, the attending physician, immediately began administering three different kinds of antiretroviral drugs to the girl. Although the mother ceased her daughter’s treatment with the drugs for approximately eight to ten months, when the daughter was tested again two years later, she showed no sign of HIV. This young girl presents a promising case for future patients. A research team from the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, the University of Massachusetts Medical School and the University of Mississippi Medical Center claim that viral remission can be achieved in an HIV+ child within hours or days of infection if the child begins antiretroviral treatments as in the treatment of this three-year-old girl.

Social and Cultural Implications

An individual diagnosed with HIV or AIDS can undertake social and cultural stigma that can be just as deadly as the disease itself, but these sociocultural stigmas are far more difficult to understand and quantify. One million people in the United States live with AIDS, but those individuals infected with HIV and scientists who research to treat and cure this disease face daily stigma. Shamers think: Why help? They’ve done it to themselves. However, this manner of thinking, whether conscious or unconscious, is not only false but wholly poisonous and crippling to social and scientific progress.

While it is true that certain lifestyles carry a higher risk of HIV infection, condemning them is like condemning people who choose to ride motorcycles because they have a higher chance of injury than individuals who drive cars. This is, of course, completely illogical. Hospitals treat brain and spinal injuries regardless of whether the vehicle involved in the accident was a motorcycle or a minivan.

However, motorcycle riders don’t have to face stigma and prejudice for their choice to ride a motorcycle. The prejudice against individuals affected by and who even study HIV/AIDS has been immeasurable, hindering progress in both fields of research and society as a whole.

Many individuals and organizations strive to raise awareness and acceptance for those affected by HIV/AIDS. Most recently, President Obama himself has recognized how this stigma negatively affects funding and therefore approved a $100 million research initiative to find new therapies for those with the disease. He also reported that the U.S. assisted 6.7 million people in receiving crucial antiretroviral drugs, greatly surpassing the goal of 6 million people he had set last year.

The students here at UGA also feel that supporting those affected by this disease is crucial to our future as a whole society. UGA HEROs raises money for children whose lives are affected by HIV and AIDS. They are one of largest student organizations on campus and in 2008 was the highest fundraising collegiate philanthropy in Georgia.