Going to the Gyno

By: Lisa Dinh

Picture yourself in a small room, roughly ten by thirteen feet.

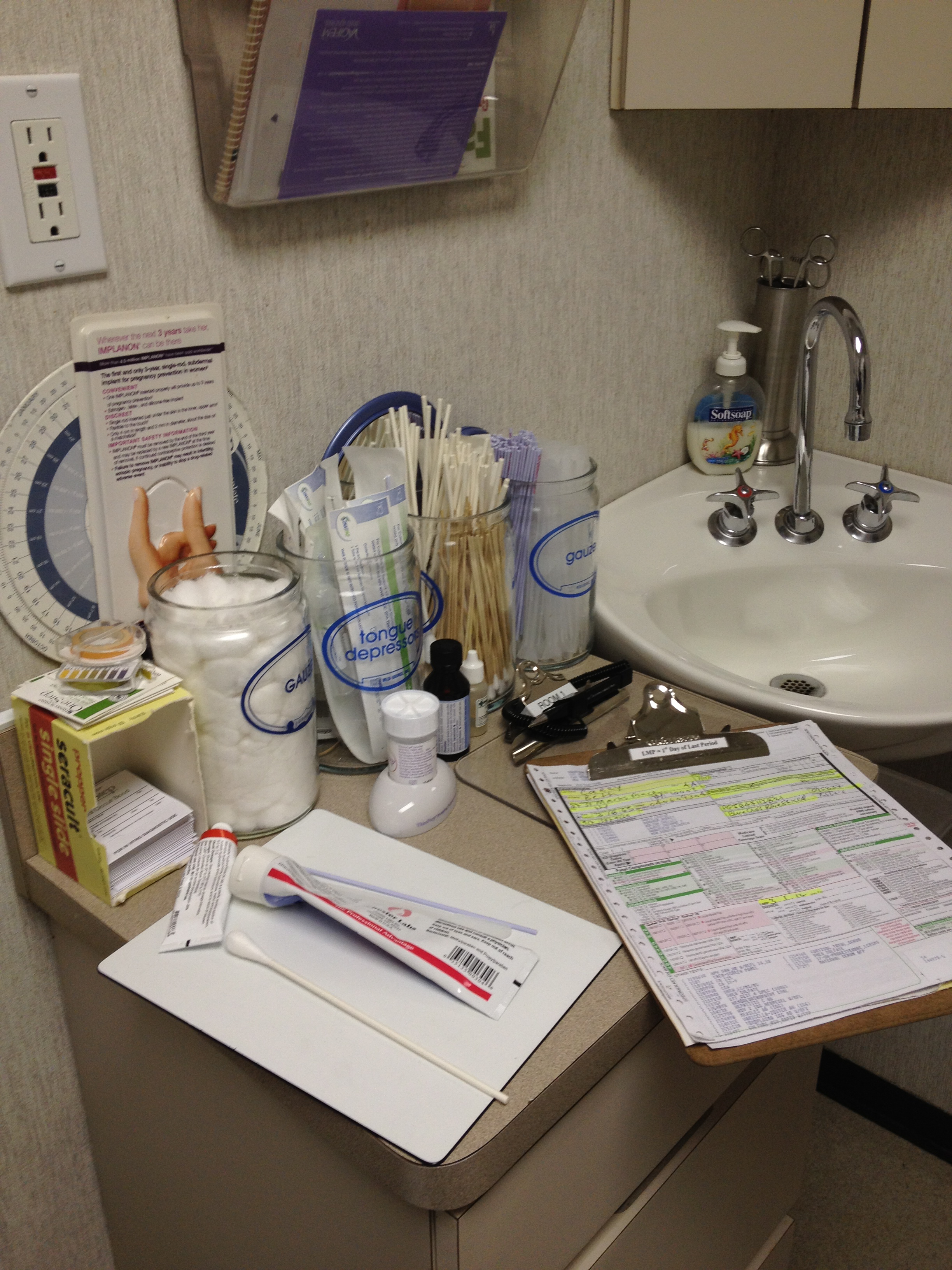

Smell: sterile, like evaporating alcohol or 8 a.m. chemistry lab.

View: white walls and laminate flooring. White crepe paper on a reclining teal seat.

Sounds: muffled voices through the walls.

Taste: your own saliva.

Touch: a little cold; a stranger’s hand.

Now picture being naked.

Naked under fluorescent lights while a metal contraption is inserted into your vagina.

Welcome to the gynecologist’s office.

Most women describe such visits as “awkward” and “uncomfortable.” And with a national average of 32.5 percent of women 18-44 years old going to the gynecologist’s office, the low proportion stacks up to the negative hype. Why do women dread going to the gynecologist?

Physicians and health practitioners now recognize the importance of women’s health. With the passing of woman’s suffrage in 1920, the nineteenth amendment declared “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged … on account of sex .2” From 1920 onward, the opinions, and as an externality, the health of women, streamlined into public consciousness. 1921 saw the founding of the American Birth Control League, recognized today as Planned Parenthood 2. 1926 brought the first successful commercialized pad2. 1931 saw the recognition of mood shifts attributed to ovulation cycles; this is formally known as Pre-Menstrual Syndrome (PMS) 2. The 1973 Supreme Court case Roe vs. Wade gave legality to first-trimester abortions; this decision remains cause for many a politician’s headache.

Women’s sexuality is now a recognized medical topic. Today physicians recommend vibrators to provide women the know-how of reaching climax- a great step from the 1800s when only women considered hysterical were “treated” with vibrators 3. Now, on the cover of your Cosmopolitan magazine at Kroger, the words “sex” and “health issues” splay themselves alongside intimate details to anyone who cares. With this trend of open disclosure outside of a physician’s office, any discomfort within seems counterintuitive. Yet those patients braving the visit seem to be walking on eggshells when speaking to their women’s healthcare providers.

Perhaps the root of the problem exists with the physicians. Women generally prefer female physicians to address their gynecological concerns. But a dearth of female physicians has been resolved since the mid-19th century when in 1849 Elizabeth Blackwell graduated from New York’s Geneva Medical College simultaneously ranking first in her class and becoming the first female doctor in America 2. Now, research conducted by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) in 2010-2011 shows that 85 percent of health professional degrees are held by women 4; the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) reports that 2009 provided 46.9 percent of female doctors in gynecology and obstetrics alone. Independent of gender, the statistics involving specialization in gynecology and obstetrics show a scarcity of professionals in the specialty. In 2010, the national ratio of ob-gyns per 10,000 women was 2.1, and 92 percent of physicians were located in metropolitan areas. With such slim selections, it’s no wonder women feel uncomfortable around their women’s health doctors. The experience must be rushed, and the narrow pool of professionals limits an individual’s ability to find their most compatible specialist.

As a career, gynecology has its quirks and perks. In 2009, CNN Money ranked a career in gynecology and obstetrics number two in highest paid careers, and twenty-two overall in their “Best Jobs” list. This ranking factors in components such as pay, job availability and growth, and quality of life. The ratings dropped in 2010 however, to fourth in pay and 100th among “Best Jobs7.” On the opposite end of the positive spectrum is the fact that 90 percent of ob-gyns have been sued at least once during their career, with an average of 2.7 claims per ob-gyn. Nearly 43 percent of ob-gyns have been sued for care provided during their residency training 7. A comparison between ob-gyn careers and Internal Medicine show that the other critical numbers: weekly work hours and years of training, don’t vary too much. The average gynecologist-obstetrician has a fifty-eight hour work week and undergoes four years of specialty training compared to fifty-five hours a week and three years in internal medicine 6.

While the overall outlook of gynecology as a physician’s specialty may not be the most lucrative, if the career really speaks to you, perhaps you’ll find yourself changing the taboo of women’s healthcare. After all, the model of “doctordom” bases itself on the simple virtue of people wanting to help those in need, and there is irrefutably a need. Perhaps if more pre-medical students took interest in going to the gyno more health-conscious women would too. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist, or even a doctor to see the causation, not correlation.