The History of Blood Transfusions

By Haley Vale

Blood transfusion is an extremely common procedure in today’s world. Every two seconds in America, a patient needs a blood transfusion. Transfusions are so common that many outside of the healthcare field know what transfusion is and how blood types work. However, in 1665, when the first transfusion occurred, the knowledge of blood circulation was still novel, having been discovered only 68 years prior. Immunology was still a new field and Gregor Mendel, the father of modern genetics, was 157 years from being born. So, how did early transfusionists have any success at all?

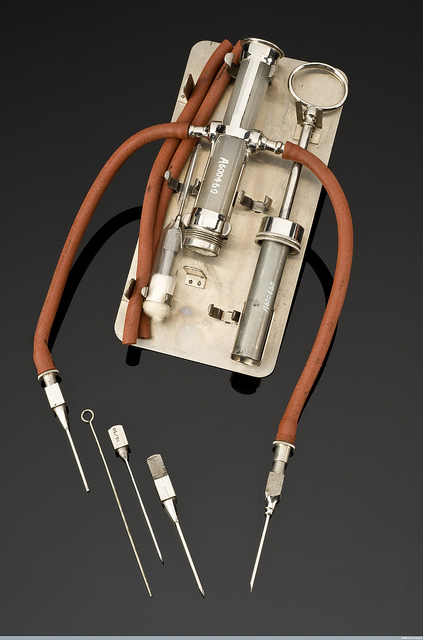

12655100485_81307792db_o.jpg: “Credit: Science Museum, Wellcome Library, London” by Wellcome Images is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The answer is, in a word, luck. During the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century, scientists used principles based off ancient Greek and Roman writings on the “humors.” With these principles, scientists conceptualized blood not in terms of its biological function, as we would think today, but as a substance that conveyed the characteristics and temperaments of the individual from whom it originated. Using this reasoning, feral and violent dog will become more subdued if transfused with the blood of a docile dog. In 1667, Jean-Baptiste Denis used this philosophy to begin his infamous transfusion experiments in Paris. Two years earlier, Richard Lower of England performed the first successful blood transfusion between two dogs. Denis began his experiments by first successfully replicating Lower’s experiments with dogs, then with calves and finally with humans. Without knowledge of antigens, immune reactions or species genetics, Denis had no idea why transfusing lamb’s blood into a 15-year-old feverish boy on the banks of the Seine would possibly succeed. Yet, the boy survived the transfusion. However, in subsequent transfusions, the recipients were not so lucky, causing the French Parliament to ban all transfusions 1679.

Landsteiner theorized that the agglutination he observed was a result of the properties of the two incompatible blood types.

Work on transfusions diminished until 1818 when James Blundell, a British obstetrician, performed the first successful human-to-human transfusion while treating a patient for post-partum hemorrhaging. After further work, Blundell concluded that transfusion should only be performed between two humans. This inspired research on transfusions to resume, and in 1900 Austrian scientist Karl Landsteiner discovered the A, B and O blood groups by observing the effects of mixing one person’s blood with another’s. Landsteiner theorized that the agglutination he observed was a result of the properties of the two incompatible blood types. Two years later Landsteiner’s colleagues discovered the AB blood group, and concluded all these blood types were mutually incompatible. It was not until 1912 that Roger Lee and Paul Dudley White to discover that O type blood could be transfused into anyone and type AB recipients could receive blood of any type. Reuban Ottenberg was the first scientist to utilize blood type matching in transfusions, and suggested that blood type inheritance was dictated by Mendelian genetics.

The work of Landsteiner, Ottenberg, Lee and White paved the way for the rise of blood depots in World War I. However, at this time, the technology only existed for direct donor-to-recipient transfusion. Blood would needed to be collected and stored outside the body in order for soldiers to be treated on the front lines. This was not possible because, outside the body, blood coagulates, making it unusable in transfusions. This problem was solved in 1915 by Richard Lewisohn who discovered that refrigeration and the addition of sodium citrate could preserve blood for a few days, allowing for storage and transport. Further developments in blood preservation that built on Lewisohn’s work led to the rise of blood banks. In 1937 Bernard Fantus established the first blood preservation and storage facility in the United States, coining the term “blood bank.”

Landsteiner concluded that this was because of another antigen present in the monkeys’ blood that the rabbits and guinea pigs reacted to. He named this antigen the Rh factor.

Despite leaps and bounds in transfusion knowledge, some patients were still reacting poorly to transfused blood despite matching blood types in transfusions. While working with Rhesus monkeys, Karl Landsteiner again made a pivotal discovery. He observed that blood from the monkeys would clot when injected into guinea pigs and rabbits. Landsteiner concluded that this was because of another antigen present in the monkeys’ blood that the rabbits and guinea pigs reacted to. He named this antigen the Rh factor. It was later determined that this Rh factor was present in some humans, but not others. The Rh factor had immediate medical importance in treating a condition known as erythroblastosis fetalis, in which a mother with Rh negative blood develops antibodies against her Rh-positive unborn child. The discovery of the Rh factor not only perfected donor-recipient matching in blood donations, but saved many infant lives.

By 1950 there were 1500 hospitals with blood banks in the United States and 31 American Red Cross regional blood centers. Since then, blood banks and the practice of transfusion have grown. Today, 30 million units of blood are transfused each year in the U.S. Preservation techniques have advanced in the last 65 years, allowing blood to be stored for up to 42 days before use. The winding history of blood transfusion is a fascinating example of how medical science grows and evolves through the collaboration of numerous scientists. Looking back at the mistakes and challenges in the development of successful blood transfusions is a reminder that moving forward in medical science is a long and arduous task that all scientists are a part of.