A YEAR IN THE LIFE OF A FIRST-YEAR MED STUDENT: ANATOMY LAB

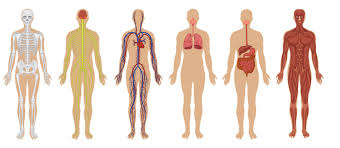

BY GRANT MERCER – Gross Anatomy lab, during which cadavers are dissected and studied in detail, is a rite of passage for most first-year medical students. For many, it is the first time seeing a dead body, much less actually touching one. The thought of dissection is daunting indeed, but this experience will provide the basis for a lifetime of patient care. “What we’re really trying to do is teach them what’s under the skin,” says Neal Rubinstein, associate professor at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. “Most physicians don’t cut into a body when they’re practicing medicine, but they have to know what’s underneath if they stick a needle here or there. Almost every physician needs to have a good three-dimensional picture of the body in their head.”

Here are the Gross Anatomy lab experiences of the three first-year medical students Stethoscope Magazineis following this year.

Leigh Anne Kline:

Wake Forest Ultrasound Lab

LEIGH ANNE KLINE – At the Wake Forest School of Medicine, anatomy lab starts the very first week of class in its brand-new cadaver lab, with windows overlooking downtown Winston-Salem. Meeting every Tuesday and Thursday morning, the medical students are broken up into groups of six per cadaver. Leigh Anne observed, “Most of us took a deep breath as we saw the bodies for the first time, as it was a little overwhelming.”

Most days, the six students are broken up into two groups – one working in the dissection lab while the other worked in the microanatomy, radiology, or ultrasound labs. Halfway through each session, the two groups switch places. Each group was told of their cadaver’s age, cause of death, and former occupation. Leigh Anne’s was a writer, dying at age 79 of hip fracture complications. She noted that the students “felt closer to our cadavers as we learned about their lives. It really set the tone of appreciation and respect for the donors as we began our learning journey with them.”

The first day in anatomy lab was spent doing skin biopsies, giving the students time to adjust to working with cadavers. The very next lab, though, students opened up the chest, beginning organ dissections. Leigh Anne said, “I’ll never forget my reaction to seeing the heart and lungs for the first time. I couldn’t get over how beautiful it was. At that moment, I was truly amazed by the human body.” As Leigh Anne is interested in surgery, she was especially excited about starting anatomy lab. She found that “the first cut was exciting. It felt like we were finally ‘doctoring’. Beginning a medical career by learning in a cadaver lab is an incredible experience.”

The anatomy lab at Wake Forest is quite intense, with the dissection lab completed in three months, usually by the end of October. At the conclusion of the Wake Forest anatomy block, a student-led reflection ceremony is held, allowing the students to reflect on the profound experience of learning anatomy through the gift of the donated cadavers. Many students share their personal reflections and each cadaver is honored in a rose ceremony.

Evan Mercer

EVAN MERCER – The Vanderbilt School of Medicine’s first anatomy session begins with a ceremony to honor the donors and to remember the significance of their lives. To further denote respect, the cadavers are referred to as “silent learning partners”, demonstrating the quiet help they are giving the medical students. Each “silent learning partner” is shared by four medical students. During each session, the students – clad in scrubs, a bib apron, and gloves – are divided into two groups – two primary dissectors and two who guide the dissection with the help of an anatomy atlas.

The anatomy lab sessions center around the classroom lessons. During the first few months, there are minimal lab sessions as the classroom emphasis is mainly on biochemistry and microbiology topics. As classroom blocks move on to study the internal organs, the endocrine and gastrointestinal systems, and finally the brain, additional lab sessions will be added to supplement the classroom studies. Altogether, Vanderbilt’s anatomy lab lasts the entire first year.

Vanderbilt’s dissections start with the back muscles as these muscles are quite large, the skin here is thicker, and a misplaced nick is less likely to damage the cadaver. Most noticeable with those first cuts is that the skin – once soft and pliable during life – is now rubbery. Like most students, Evan worried initially about cutting too deeply, but observed that “you can feel the change in texture when you pass through the layers of skin and encounter muscle.”

Vanderbilt Dissection Lab

photo credit: www.displaydevices.com

Evan’s “silent learning partner” was a male who succumbed to B-cell lymphoma. During the dissection, the students found tumors in the man’sshoulder, ranging in size from a quarter to an egg. Each group’s “partner” yielded surprises. In one group’s cadaver, a mechanical heart valve was located. In yet another body – a man with jaundice – the preservation chemicals had mixed with his orange skin color to give the cadaver a greenish hue.

While a scalpel is used to open the skin and for the organ dissection, bones are a different matter. To remove the spine, Evan welded a hammer and chisel. A bone saw was used to cut through the ribs to reveal the heart and lungs.

Initially, Evan felt that it was “hard to see the person’s face, a reminder of the life they led before they came to rest on the table before you. Once you start making the cuts, though, the dissection process takes all your focus.” Evan added that at first, he was “skeptical about how much anatomy lab would help to understand the material. Why not just have more lectures? In reality, the body is messy, filled with dull-colored, grayish-red organs – nothing like the color-coded anatomy diagrams found in science books. The sessions in the lab have done wonders to help me better understand anatomy.”

Andrew Hey:

University of Louisville School of Medicine

ANDREW HEY – At the University of Louisville, anatomy lab is presented as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, deserving of the utmost respect. All of the cadavers were Louisville residents having died within the last two years. The initial instructions focused on being respectful of the cadavers at all times, including not taking any pictures in the lab, avoiding any cadaver-related humor, and not taking any food or drinks into the lab.

Six medical students, subdivided into two groups, are assigned to each cadaver. Working in the lab from 9:00 to noon for three days every week, one group dissects for the majority of that time, reserving the last 30 minutes to teach the other group about what anatomical features were worked on that day. Every other lab day, the two groups alternate these roles. Andrew’s group nicknamed their cadaver “Harry” because of his buzzcut hairstyle. He noted that “naming him allowed us all to connect to him on a more personal level.”

Forty cadaver tables, arranged in five rows of eight tables, fill the large, always spotlessly clean anatomy lab. The room’s closets are filled with skeletal displays and brain samples. Every evening the cadavers are sprayed with a formaldehyde-like preservative, the odor still lingering in the air during lab time. Andrew’s first cuts were to Harry’s neck and back. “Initially, I was very delicate in working with the scalpel. I learned very soon that this technique was too time-consuming. There would not be enough time to remove the fascia and fat from structures. I quickly learned how to cut through tough structure more quickly.”

Andrew’s first reaction to seeing “Harry” for the first time was sadness, thinking of a life lost. He added that now whenever he sees Harry, he is “no longer sad, but grateful for his donation of his body to help future doctors. I like to imagine that he knows his impact on the world of medicine and is looking down on us with a jubilant smile.”

Louisville’s anatomy lab lasts six months. During that time, the medical students will have dissected or isolated every single muscle, bone, organ, nerve, artery, and vein in the human body.

NEXT UP: MEDICAL SCHOOL CLASSES