Women in Medicine: The Legacy of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

By: Erica Lee

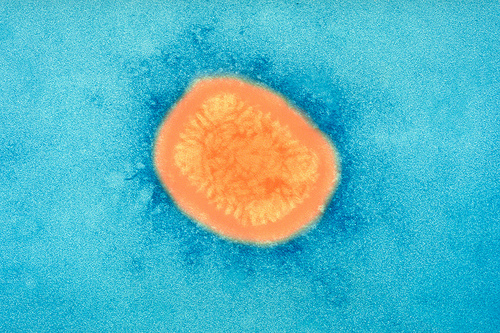

Smallpox: a devastating but distant disease . The last naturally-occurring case was in 1977, and the few remaining samples of the variola virus stay safely locked away in the CDC in Atlanta and the Vector lab in Siberia. Smallpox once ravished the known world, slaughtering two-thirds of its victims and scarring its survivors for life.

To Mary Montagu, a world without smallpox would seem like a cruel joke. She had watched her brother’s body blister and his strength fade until he died. She herself contracted the disease and survived, although it robbed her eyes of their eyelashes and marked her famous beauty with pock marks and scars. She wrote that the disease forced her to “live, in some deserted Place,/ There hide in shades this lost Inglorious Face.” Sobered, she left England with her husband, who was the ambassador to Turkey. There she witnessed a strange practice: variolation.

Variolation was the precursor to vaccination. The Turks called it “engrafting.” In a letter to a friend in England, Montagu described this strange practice. In September of 1717, Lady Montagu watched an old woman perform the operation. The old woman came with “a nut-shell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox,” meaning the pus from smallpox macules. She opened her patient’s vein and placed the pus inside with the needle and repeated this process with four more veins.

Intrigued, Montagu watched the patient’s recovery. He seemed to be in perfect health until the eighth day, when he contracted a fever and took to his bed for two or three days. He formed only twenty or thirty macules on his face, which left no scars. In approximately eight days, he made a full recovery: now immune to smallpox.

She observed as many operations as she could. “Every year, thousands undergo this operation,” wrote Montagu, “and you may believe I am well satisfied of the safety of this experiment, since I intend to try it on my dear little son.”

The embassy physician, Charles Maitland, inoculated little Edward Jr., who survived the procedure without any negative effects. When Montagu and her family returned to England, she raised awareness for the procedure by having a physician inoculate her three-year-old daughter in a public.

Montagu didn’t stop there. She believed the whole of England should be inoculated and set out to abolish the stigma surrounding the operation.

When her husband went to the King’s court, she befriended his wife Caroline, Princess of Wales. Montagu suggested to her new friend that prisoners might be willing to be inoculated, which Caroline promptly arranged. She offered seven criminals who had been sentenced to death a choice: death by the gallows or a chance at another life after the inoculation. All chose to be inoculated and survived. Their faces bore the scars of the smallpox virus, but they were free.

Emboldened by her success, Montagu requested for six orphan children to be inoculated: they all survived. In 1722, she even convinced King George VI to inoculate two of his grandchildren. These operations were also successful.

Because of Lady Montagu’s tireless work, smallpox inoculation became a commonly accepted practice. Even though it still carried a small risk of infection, it saved countless lives. Her innovation paved the way for a less risky inoculation using cowpox, first implemented by a scientist named Edward Jenner.