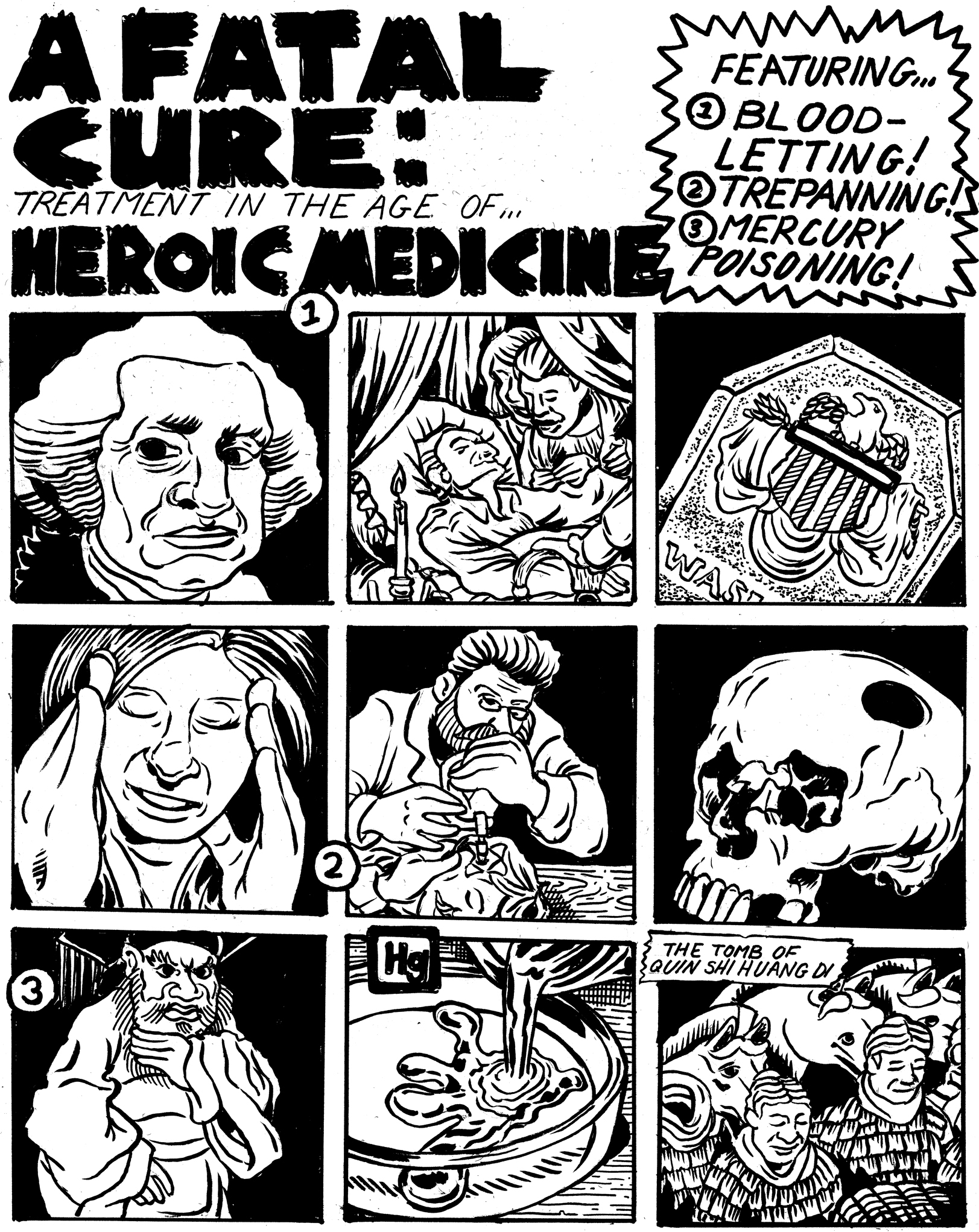

Throwback: A Fatal Cure: Treatment in the Age of Heroic Medicine

By: Erica Lee

George Washington was dying.

For two days he had gone out onto his plantation in the snow and sleet, overseeing farming activities and designating trees to be felled, even staying in his wet clothes to be on time for dinner. He was a robust man. He put it out of his mind.

Washington fell asleep with a cold and woke barely able to breathe. His friend tried to give him molasses, vinegar and butter to calm his throat but this vile mixture only caused Washington to convulse and nearly suffocate.

Instead, he drew up his sleeve and presented the veins there. He ignored his wife’s warnings. Washington was a firm believer in the practice of medicinal bleeding, or venesection.

“Don’t be afraid,” he said when the lancet punctured his skin.

“The orifice is not large enough. More, more.”

Twelve hours, three doctors and four bleedings later, Washington got his wish. Five pints of his own blood had been drawn from his veins, more than half of the blood in his body. He passed away that night at the age of 67. He left behind a mourning widow, solemn friends, a grieving nation and the fuel for a malpractice debate that would last for two centuries.

Washington and his doctors merely followed the common medical beliefs of the time, in an age of medicine that would come to be known as the heroic age. Doctors in this age believed in strange, unscientific cures that were often more dangerous than the original disease.

Respiratory problems? We’ll bleed you dry.

Headaches? We’ll put a hole in your skull.

The act of drilling or scraping a hole into a human skull, or trepanning, has been around for millennia. Skulls with the trademark bores or “burr holes” up to two inches in diameter have been found dating from the Neolithic period onward. Early physicians believed trepanation would cure mental disorders, epileptic seizures demon possession and, ironically, migraines. Fantastically, many patients survived the procedure. Over two-thirds of the skulls found show bone regrowth around the incision site.

Scared of death? STIs? We’ll poison you.

Heroic medicine also had tinctures, tonics and salves often made from poisonous ingredients. One popular ingredient for these tonics was mercury, whose strange properties have always been a source of fascination and wonder. One person fascinated by the metal was China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang Di. He believed that mercury would make him immortal. Every day, he drank mercury tonics and swallowed mercury pills. When he grew old and sick–no doubt from the overexposure to mercury–he even ordered himself to be buried in a tomb flowing with mercury rivers.

Thankfully, after the mid-nineteen hundreds, modern research replaced these methods with more scientific, if still sometimes imperfect, methods of curing disease.