THE INTERGENERATIONAL EFFECT: HIV/AIDS ORPHANAGE POPULATION

Children at Sele Enat orphanage

BY EMMA ELLIS – According to Ethiopian tradition, children recieve their second name from their father. Like many cultures, this custom highlights one’s paternal lineage, offering information about an individual’s ancestral history. Yet, although Nebyu Sele Enat and Halwet Sele Enat both share the same last name, they are not brothers. At least, the two are not biologically related. The name Sele Enat instead refers to the orphanage they were brought to on the day they were abandoned by their parents. It was then that they became two out of the hundred thousand Ethiopian children that are orphaned each year from the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

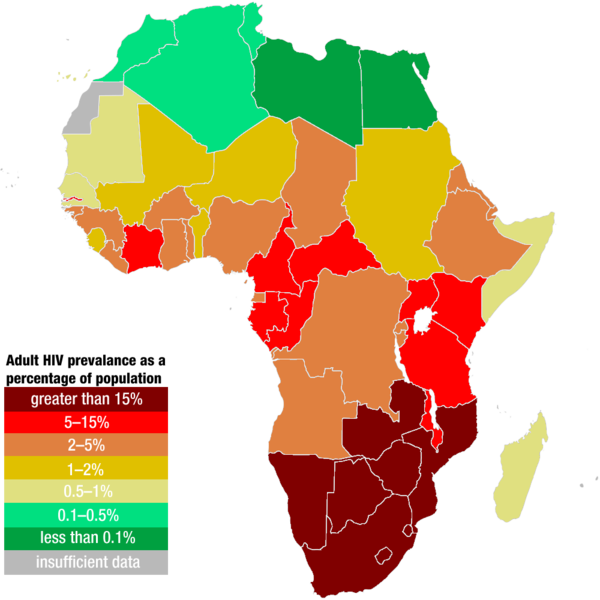

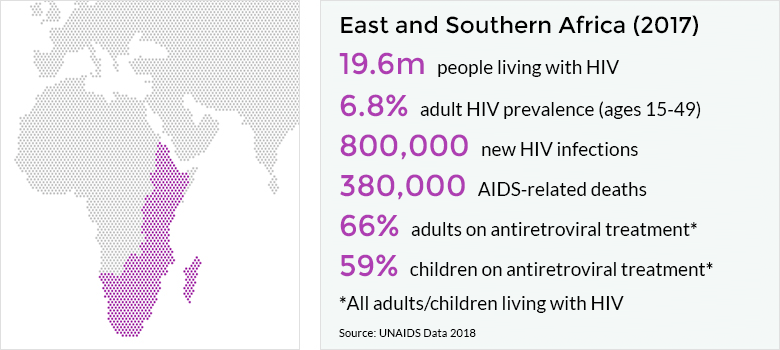

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) occurs after HIV, or human immunodeficiency virus, weakens the ability of the body’s immune system to locate and destroy infections. HIV largely works by minimizing the number of functioning T cells in the body. While the body can never be completely rid of HIV, the development of AIDS can be prevented through proper medication. However, in order for treatment to be effective, individuals must have the resources available to receive their diagnosis and be aware of their need for medical assistance, as well as have access to the medication itself.

Melissa Fay Greene explains the limitations in offering diagnoses and treatment in her book, There is No Me Without You: One Woman’s Odyssey to Rescue Her Children. Greene’s novel explores the causes and effects of the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS on Ethiopia’s most vulnerable population: children. Greene specifically charts the story of Haregewoin Teferra, a woman who started an orphanage in Addis Ababa after suffering from the loss of immediate family members. Greene’s book elucidates the hidden intergenerational effect of the HIV/AIDS epidemic beyond the physical symptoms.

Melissa Fay Greene explains the limitations in offering diagnoses and treatment in her book, There is No Me Without You: One Woman’s Odyssey to Rescue Her Children. Greene’s novel explores the causes and effects of the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS on Ethiopia’s most vulnerable population: children. Greene specifically charts the story of Haregewoin Teferra, a woman who started an orphanage in Addis Ababa after suffering from the loss of immediate family members. Greene’s book elucidates the hidden intergenerational effect of the HIV/AIDS epidemic beyond the physical symptoms.

The children that arrive at Haregewoin’s orphanage have backstories similar to that of Nebyu and Halwet Sele Enat; their parents either died or became too sick from HIV/AIDS to raise them. Care from extended family members is often limited financially or physically, leading to the high population of children in these types of facilities.

Amid the orphanages, the children’s medical statuses are varied; some acquire HIV from their mother during birth while others are fully healthy. Among those not-infected with HIV, difficulties arise in offering sufficient resources and attention for a stable upbringing. Even after leaving the orphanage, HIV/AIDS orphans suffer from increased amounts of discrimination, affecting their ability to fully reintegrate back into society. Stigma in the community largely stems from fear of contracting HIV, as Greene points out that the mechanisms through which it spreads through a population are often misunderstood.

With international adoption recently outlawed in Ethiopia, the country is even more pressed to locate a solution that will alleviate the strains felt by local orphanages. The long-term answer perhaps lies within the age-old metaphor of turning off the leaky faucet rather than mopping up the water already on the floor. By increasing the accessibility of diagnosis and treatment of HIV, AIDS can be avoided, minimizing the loss of the parents. Education, in particular, is key, as only 50% of Ethiopian women and 69% of men understand the methods of limiting exposure to HIV. Regardless of the solution, the HIV/AIDS orphan population offers a second dimension to the epidemic that calls for greater public acknowledgement of the issue.

With international adoption recently outlawed in Ethiopia, the country is even more pressed to locate a solution that will alleviate the strains felt by local orphanages. The long-term answer perhaps lies within the age-old metaphor of turning off the leaky faucet rather than mopping up the water already on the floor. By increasing the accessibility of diagnosis and treatment of HIV, AIDS can be avoided, minimizing the loss of the parents. Education, in particular, is key, as only 50% of Ethiopian women and 69% of men understand the methods of limiting exposure to HIV. Regardless of the solution, the HIV/AIDS orphan population offers a second dimension to the epidemic that calls for greater public acknowledgement of the issue.